Do not be troubled about anything; let us strive to please God alone.

SAD CHILDHOOD

The Marchioness Magdalene Gabriella of Canossa was born in the evening of March 1, 1774, in Verona, the beautiful city of the Scaligeri family. She was the third child of the Marquis Ottavio and his twenty year old wife, Countess Teresa Szluha. Her birth was no mоment of joy for her parents, but a bitter dissapointment. They had been expected the son.

The baby was baptised the next day in the parish of San Lorenzo.

Magdalene stood out among her brother and sisters for her vivacious, open character, both affectionate and strong.

Unfortunately, the harmonious development of a tranquil childhood was interruted by a family tragedy which suddenly befell the Canossa house. On October 5, 1779, Marquis Ottavio had a seizure while on excursion toLessini hils. He was olny 39 years old. He died the next day.

Unfortunately, the harmonious development of a tranquil childhood was interruted by a family tragedy which suddenly befell the Canossa house. On October 5, 1779, Marquis Ottavio had a seizure while on excursion toLessini hils. He was olny 39 years old. He died the next day.

Just a few monhts later, Magdalene and her brother and sisters were hit by an even worse tragedy: to loss of their mother. On her husband’s death, teh 27-year-old Countess Teresa had found herself alone,the only woman in the Canossa household, with four men to look after, in addition to her own five children. Her knowledge of Italian language was only fair. her mentality was opened and very different from that of the Marquises which was somewhat rigid and conservative. She married Marquis Odoardo Zenetti of Mantua, abbandoning to their fate her five small children, of whom the oldest was nine the youngest only two.

Yet, Countess Teresa was attached to her children. On many occasion later and, in different circumstences, Magdalene would repeat: “mother loved her children very much”. In fact, she kept up a discrete and affectionate correspondence witn her children. Who will eve be able to unveil the mysteries of a woman’s heart?!

Magdalene was 7 years old. She shut the traagedy of that incomprehensible separation un in her heart and kept it there forever in absolute and respectful silence.

A DISCONCERTING GOVERNESS

The choice fell on a French woman, for at that time it was felt that only the French were endowed with the necessary competence and “savoir faire” for preparing the daughtersof noble families for life in society.

Unfortunately, Francesca Capron soon revealed hersefl to be an unscrupolous woman. In the beginning, Magdalene, a liveli headstrong child, seemed to be her favourite. She tought that her antics and temperament were qualities necessary to give that touch of originallity considered desiderable in a future lady and, instead of educating and correcting the child, encouraged and praised her.

Albeit confusely, the child felt that there was something cowardly in accepting an education that was no honest. On the occasion, when her teacher suggestet that she should tell a lie to get out of a well-deserved punishment from the uncle, she refused to obey. When, on another occasion, a noble woman from Venice came to stay in the Canossa huosehold, having been entrusted by the children’s uncle with the precise talk of examining his nieces’ behaviour and progress in their studies, Magdalene again got herself into trouble. The noblewoman and Miss Capron were in one of the rooms of the palace talking about the best way of teaching catechism. The Venetian lady expressed some doubts on the value of the method based solely on learning by heart. The conversation started to become animated when Magdalene suddenly burnst into the room. The guest, who didn’t want to, in any way, lessen the prestige of the teacher in the eyes if her pupil, turned to the little Marchioness and warned her: “Woe betide young ladies who lear catechism in the same way as they learn grammar, history and geography!”.

Magdalene liked these words of warning so much that she ran to her bedroom to write them on the front page of her catechism book. Some time later, Miss Capron noticed the words and interpreted the fact that the child had copied them in her catechism book as a sign on insolence towards her.

From on then, Magdalene became her target. The child was persecuted for years, the victim of increasing unfairness and at times real cruelty, so much so that her girlhood became increasingly unhappy.

What was surprising, and was taken note of by almost all those who witnessed it, was she maintained absolute silence. She never rebelled, nor lacked in respect or obeddience. She knew how to suffer with a maturity and a strength far beyond her years.

Her older sister Laura could not understand why Magdalene said nothing. She indignantly urged her sister to tell their uncle about the very unfair treatmente she was being subjected to. The young Marchioness would simply repeat: “Madame is right. I am the one who is bad”, adding: “With this guardian angel, I will never bo able to go the wrong way”.

If, however, she knew how to remain silent when it was a question of her own sensitivity, she knew that she had to talk when it came to preventing something really bad from happening. The two older sister had an Italian teacher, a certain Giuseppe Mindini, who was on excessively close terns with the governess. One morning Magdalene firmly announced to Miss Capron that neither she nor her sister Laura would attend the lesson of a man whose ambiguous words were endangering their purity. The governess knew immediately that her pupil would not give in: she knew too well that, being a real Canossa, there would be no going back on her decision.

Hence she advised Marquis Girolamo to dismiss Mr. Mondini. Soon after, she also resigned and, in April of the same year, 1798, she married the professor. Magdalene, who had already forgiven and forgotten the way Madame Capron dealt with her, sent them a wedding present.

THE MYSTERIOUS ILLNESS

The young Marchioness at the age of fifteen suddenly became ill, and was brought close to death by a mysterious malady. After days of anguish and fear, suddenly the fever disappeared just as it had come. It was then that she felt an acute pain in her leg. A severe attack of sciatica kept her nailed to the bed for a long period of time, causing her much suffering, most of all when medicated with caustic substance.

The fear of physical suffering was coupled with another fear: the young girl?s face would be forever pox-marked as a result of the disease. Her relatives were distraught, but the patient reassured them: ?I don?t have to look pleasing. I am going to be a nun.?

When the worst finished, her body had been harmed for ever: from that time on she was weak in the chest and her movements were hindered by a contraction in her arms, which rendered the rest of her existence painful.

Magdalene experienced her solitude with a mixture of anxiety and satisfaction; it accustomed her to interior dialogue, und aroused within her a desire for a more profound and complete peace.

THE DIVINE CALL

Once she had recovered, Magdalene felt more strongly and clearly than ever before that divine call which she had already felt during the very early years of her life. The fever which had blocked her limbs, made the attraction of an ephemeral happiness disappear like a spell in the mist.

Writing at the age of seventeen to Father Federici, a Domenican resident in Treviso, Magdalene herself related the story of her vocation. She revealed that she had felt the first invitation to give herself totally to Christ in a strict religious order ?at around the age of five.? But then the type of education she had been given, the comments of her relatives who had made allusions to various advantageous matches for the family, the compliments she received, the attraction of fashionable society had been a strong threat to her religious vocation around the age of fourteen and fifteen. The illness had saved her from the falsity of worldly illusions, so attractive at that age, and taken her decidedly towards God. It seemed then that ?she desired or sought? no other than Him. At the same time, she felt very strongly, as she herself put it, ?the inclination)) of charity towards the poor, the sick, the orphans, those without love.

And as the months went by, God?s call for a total consecration became increasingly persuasive. Magdalene would have liked to answer immediately, but the thought of renouncing the practice of charity, which monastic life would have imposed on her, made her hesitant and uncertain.

Who would have helped the many poor people who each day flocked to the entrance of Canossa Palace? It is true that in the convent, being able to converse more with God, she would have prayed for them too; but they also needed her bread, her clothing, her help, her smile to help them go ahead with their wretched daily existence.

She felt that the cloister would have clipped the wings of her initiatives of charity.

For this reason, she was so hesitant and preferred to say nothing at home. Her family was convinced that sooner or later she would have set her heart on one of the young descendants of noble families who frequented the parties and receptions held at the palace, and accepted some serious proposal of marriage, such as that of a young descendant of the Borromeo family from Milan.

But when, at the theatre, her escort complimented her in a way not entirely without significance, she felt the time had come to openly declare her vocation.

She took the opportunity while the family was at table discussing a very good marriage which had recently kept all the drawing rooms of the city buzzing and had been considered an exceptional match by all. Half enigmatically and half jokingly, she revealed that she too had received some wonderful proposals and had not wished to miss the opportunity. In fact, she had given her consent. Her uncles, as well as her sisters, could hardly believe their ears. They were even somewhat disconcerted. Such behaviour was unthinkable in a real lady. Marriage was a family affair and not a personal choice. It was the relatives who chose, or at least approved, the spouse. Magdalene?s statement could only have been a joke.

But when, with a glimmer of joy in her eyes, she stated resolutely that she had chosen for herself the most beautiful, wealthy and good man in the world as her spouse, Jesus Christ, those sitting around the table felt their hearts torn by contrasting sentiments of admiration and sadness. Magdalene?s choice was undoubtedly an expression of piety and noble sentiments, but it also meant that sooner or later she would be leaving the family home and her relatives. This was something they could not resign themselves to. They loved her too much for that, they were too fond of her. However, while trying to prevent her from taking this step, they soon realised that the battle was lost and that Magdalene would definitely be leaving them.

They were soon aware that her resolution was not just a passing whim. It was her response, both courageous and generous, to the mysterious invitation of a greater love. Her religious vocation ?noble, obstinate and heroic? had matured in her trial, had passed through the crucible of suffering. She was now ready to overcome any further difficulty, to surmount any future obstacle.

Alongside her religious vocation, the Lord, in the hour of sorrow, had made her feel very strongly another special inclination, that of charitable service. For it was then that the ?inclination? for works of charity budded in her spirit. In the solitude of her illness, her thoughts often went to the many sick who were without help and comfort. And, when she was ill-treated by her governess, her, exquisite sensitivity helped her understand the sad tragedy of many young people without love and, without help, of many young girls without guidance. It was then that she resolved to assist them.

With the lesson of pain, Divine Providence was” preparing Magdalene for the pressing apostolate of charity, at a time in which old Europe and, particularly, Italy was plunging into war and misery, social and religious unrest. In this situation, the young and the poor would be the most numerous and defenceless victims.

THE CLOISTER

After her official announcement, Magdalene took advantage of the imminent marriage of her sister Laura to leave the family for the first time. She asked her uncles to allow her to retire to the Monastery of the Terese, outside Porta Romana in Verona, so as to avoid the distractions caused by preparations for the marriage. In that way she would be better able to test her vocation. Her uncles suggested that she should first meet three ex-Jesuits of great culture and piety who would examine her vocation to the religious life. All three, independently of each other, advised her not to go into the convent. However her confessor, Father Stefano of the Sacred Heart, a Carmelite, urged her to go into seclusion immediately. As always, Magdalene obeyed. She entered the ?Terese? on May 12, 1791 and remained there for some months. It was an unusual experience: torn between attraction and unrest, between light and darkness. She liked the daily life of the nuns: prayer, fasting, silence. But two things she found oppressive: ?the monastery grating and the fact of not being able to be directly engaged in works of charity.? She discussed this openly with Sister Luigia della Croce, one of the most enlightened sisters of the convent, who soon afterwards became prioress. She candidly opened her heart to this ?holy nun? who clearly perceived that the young Marchioness was called not to an enclosed life but to an apostolic one. Her path, was to take her elsewhere. But where? Sister Luigia herself did not know. All that she felt very clearly was that Magdalene was not made for the cloister. She told her so, openly, eventhough she was sorry that they had to part. She persuaded her to go home.

The young Marchioness returned to her family but only for a short time. Father Ildefonso of the Conception, the prior of the Carmelites of the Annunciation, who had temporarily taken the place of Father Stefano as her confessor, perhaps dazzled by the unusual virtues which he discovered in Magdalene, and perhaps unconsciously driven by a pride in his institution, not only advised her to join the Discalced Carmelites of Conegliano, but ordered her to do so. Again Magdalene obeyed. Before leaving for what she believed was going to be her final home, Magdalene felt a strong desire to see her mother again and to receive her blessing. They met at Valeggio sul Mincio, in the villa where her eldest sister Laura, a year earlier had become the Countess Maffei, lived. They were both extremely moved. When the time of parting came, Magdalene knelt down before her mother, asking for blessing. After her return to Mantua, the countess, recalling the meeting which was to be the last with her favourite daughter, kept repeating amid tears: ?Magdalene is a saint. A saint!?. The Carmelites of Conegliano were happy to have the young Marchioness of Canossa. And Magdalene, eager, as she wrote in her Memoirs, ?to be called ?Discalced? by the Lord? believed that at last she had found her vocation. She had prepared herself for the Carmelite life, by carefully reading the Rules ?which had given her such satisfaction, making her more determined than ever before to join the convent?.Admittedly she still strongly felt ?aversion for the cloister? and was tormented by the thought that ?in that place..she would not have been able to prevent sins nor help save souls.? But she was also convinced that it was just a temptation and was determined to overcome it ?even at the cost of her life?.

She stopped at Conegliano for only three days and then set off for Verona ?determined to come back to take the habit?.

But God, ?through some unforeseen means?, the exact nature of which we still do not know today, prevented her from returning. Magdalene, though unwillingly, left the Carmel. In town there was much amusement at the volatility of the young Marchioness of Canossa. Her family also had some doubts as to her strength of character.

A letter from Sister Luigia, who had understood her plight, arrived at the right time to cheer her up. She urged her to know how to accept such bitter disappointment from the hand of the Lord as a ?means of sanctification?, and reminded her: ?The fact that God has shown you clearly that He does not want you as a Discalced nun, does not mean He refuses you as His bride.?

Magdalene found this convincing, though she could not see how her future nuptials were to take place.

DON LIBERA: THE ENLIGHTENED GUIDE

Sister Luigia, an expert in the problems encountered by religious souls, felt that a change in her spiritual guide would be a way of helping Magdalene to overcome the uncertain situation in which she had found herself. And she suggested Don Luigi Libera. He was a diocesan priest of around fifty who was confessor in various monasteries and very highly esteemed in town.

The young Marchioness ?placed herself trustingly in the hands of this holy priest who had a great spirit of prayer.?

He was Magdalene?s guide for approximately nine years. His delicate spiritual relationship with the young girl helped her to clarify to the full her vocation and to proceed confidently towards her future mission of charity. He met her often at Canossa Palace and they both exchanged many letters. Unfortunately, but understandably, none of Magdalene?s letters have reached us, whereas there are about sixty-eight of Don Libera?s letters to her.

Through this correspondence we can reconstruct Magdalene?s spiritual progress from July 1792, immediately following the episode of Conegliano, to December 14, 1799, the date of the director?s last letter. He died, too soon, on January 22, 1800. Don Libera?s method appears to be very different from that of the Carmelites. He used understanding rather than authority, respecting the independence and freedom of the penitent rather than forcing his will on her, giving her orders.

His first act was to advise Magdalene to ?lead a very withdrawn life within her own home for a year and pray fervently to know God?s will?, without making any decision as to her future. He then openly told her that he could not see that she was in any way called to the Carmelites? life and, while waiting to understand her situation more clearly, he urged her to devote herself to the normal activities of a numerous family.

She was immediately called to take care of her great uncle Francesco whose health had suddenly deteriorated. Up to the time of his death, which occurred two days before Christmas 1793, she was his loving and irreplaceable nurse.

At the request o f her uncle, she was also asked to take care of her two younger sisters, Rosa and Eleonora, and accompany them on the first steps of their social life. Don Libera encouraged her and gave her useful advice on how to guide her sisters, urging her to avoid the always harmful extremes of excessive severity and laxity. When he believed it fitting, he allowed her to accompany her sisters to the theatre and suggested that she should not stop them from going to dances for ?it was better to fit in with their station in life…and not make religion too repulsive to the laity.? Where there was no ?absolute evil, it was good to comply.?

Don Libera?s realism and optimism were in contrast with Magdalene?s rigor and scrupolosity. The wise director patiently but firmly set about freeing her from this sad excess.

He assured her that she was living in the state of grace, that her path towards sanctity was consistent and firm, that she should not concern herself with her recurring fear of damnation: ?We should not allow ourselves to be slaves of scruples…; blessed are those who live in the fear of offending God, but let us ensure that our fear be filial and reasonable, because it is born of love.?

Magdalene reiterated her fear of not having been understood: she had the sensation that if both her director and confessor knew her well, in depth, they should have realised that she was a great sinner. She was convinced that it was she who did not her true self.

Don Libera told her insistently that her conscience should be at peace. With serene irony he wrote: ?Can everyone be wanting to betray you?…I know full well how bad you are, but should we despair for this?…My daughter, I don?t consider you as an angel from heaven but I cannot bring myself to believe that you could have committed so many sins.?

To pacify his penitent, Don Libera frequently cut her short and prescribed ?generous and ready obedience, an effective means of conserving one?s peace of heart…Have trust…in this beautiful virtue of obedience, practise it with all your commitment and in the simplest way possible.?

He required obedience also regarding temptations against faith which tormented Magdalene for several years, temptations against the existence of God, against the truths of the Creed: ?To counteract your thoughts against faith, pray to God three times a day expressing your belief in what the Holy Church believes and your will to die in this faith: in peace and quiet, without being scrupulous about your every thought.?

Another way of expressing obedience was to renounce completely her desire to go into the convent, which from time to time she continued to feel growing inside her. By the end of the first year of trial, Don Libera told Magdalene that he was certain that God ?was not calling her to be a ?Disclaced? ? and that he could not discover in her ?any certain sign of vocation to the religious state?; likewise ?he did not see her as being called to matrimony?. Instead he urged her to wish only that which the Lord wanted from her, and to continue to be ready to sacrifice her every desire and will to accomplish the Will of God.?

This divine Will was expressed in the events concerning her family which, for example, required her to follow more closely her sister Rosa, who was about to be married, and to be an element of peace between the members of her family, divided over questions of inheritance. He advised her to take over the running of the big house, even though with certain limitations, since there was no female hand able to do so.

He asked her to give up a consecrated life in the cloister for a service of charity in the family and in the world. Consecration to God did not necessarily involve segregation from the world but loving acceptance of God?s will. And in the ?world? she would be able to do that good which, in the monastery, she would have been prevented from doing. In fact he wrote: ?My daughter, I will never cease thanking the Lord for giving me the light to keep you in the world. For you it is hard, but let it all be done to the glory of the Lord and be assured that, in the present circumstances, in the segregation of the cloisters you would not be doing the good that you can do at home.?

The wise director, who was familiar with the young Marchioness? need to act, had gradually approved the different charitable activities which she had started in the city. A fairly vast network had developed which was increasingly and carefully analysed and completed, as part of a ?Plan? which anticipated the creation of a permanent institution for the poorest and the forgotten. It was an ?imaginary dream?, for now, jealously held in custody in Magdalene?s heart, but which contained in embryo her future mission of charity. When she illustrated it to the director, she met with his complete approval: ?…I urge you with all my strength and, if you wish, I even order you to give your whole heart to the institution… ?

Don Libera encouraged her but was, at the same time, careful that her activity should not become activism. Hence he invited the young Marchioness to frequently report to him on her spiritual life. He urged her to pray and especially to devote herself to mental prayer which should become simple and true contemplation. He advised her to dedicate much space to prayer, without neglecting her family duties. He insisted that she should set aside a fixed time for the practice of daily prayer. He recommended the use of ejaculations which favour an attitude of familiarity with the Lord. He encouraged her, contrary to the custom of the time and the general jansenistic mentality, to frequently, even every day, receive Holy Communion: ?the real life of the soul, the food of the strong.? He prescribed repeated visits to the Blessed Sacrament, as vital moments in her day. Eucharistic prayer was, for Don Libera, a source of great spiritual energy. It was like a fire constantly lit in the house of God to keep kindled a heart that wished to love the Lord and her brothers.

In trying to solve the problem of her vocation, and also to proceed confidently towards virtue and sanctity, he ardently urged her to grow in the love of the Virgin and to entrust herself to her, as a daughter. Devotion to Mary will be a characteristic of Magdalene?s spirituality and will accompany her whole life in a simple and loving crescendo.

Accustomed to adhering to God?s will, through events which touched her directly, and strengthened by the constant practice of solid piety, the young Marchioness succeeded in overcoming the greatest trial which the Lord asked of her, just when she believed she was free to try to fulfil her ?dream?. In November 1797, the very young wife of her uncle Girolamo, the Countess Claudia Maria Buri became ill. On her death-bed, she entrusted to Magdalene?s care her baby, Carlino, who was just a few months old, begging her to look after him and be his mother. In the mystery of death, which comes only from God, Magdalene saw clearly His will. She accepted to be ?mother? and to continue to remain at home, awaiting other signs from Above. Her vocation was to give herself to others, to place herself totally at the service of those who were in need.

FRENCH REVOLUTION

In March 1796, the French, led by a 27 year old general, Napoleon Bonaparte, had invaded the peninsula to defeat Piedmont and Austria. In the meantime, in accordance with the orders received from his government, he would set fire to Verona. The division of General Massena was already on its way for this purpose, and would be arriving in the city the following day. One can imagine the clamor such a threat aroused amid the population of Verona. Angry and frightened, many citizens fled from the city immediately. Magdalene and her brother and sisters escaped to Venice where they stayed more than a year.

The French entered the city on June 1, and marched through the streets as liberators, greeted with consternation by practically the entire population ?which saw in them the enemies of the faith and the disturbers of public peace.? Two months later, the Austrian troops arrived and they too marched through the streets as liberators. Nine days went by, and the French appeared on the scene again.

The people of Verona, tired of the inertia of Venice which, though informed of the situation, took no action to remedy it, took advantage of the fact that Napoleon was absent. The military forces were under the command of general-brigadier Antonio Maffei, Laura Canossa?s husband. The farmers he had managed to muster up to join forces with other volunteers in the city, met with considerable success; to the point that they besieged Brescia.

The French soon came back onto the scene, forcing Maffei to abandon the occupied territories, and the city was prey to every type of pillaging and abuse. This was too much for the severely tested patience of the citizens of Verona; they could bear it no longer and, on Easter Monday, there was a popular uprising, which has gone down in history as the Pasque Veronesi (The Veronese Easters). The French soon got the better of the revolters and, having restored law and order, took their revenge on the citizens.

Through 46 noblemen were taken hostage, including Bishop Avogadro and Laura Canossa?s husband, Count Maffei. The bishop was saved by a single vote. And Maffei, too, miraculously escaped death. On receiving such sad news, the Canossa family in Venice lived in constant anguish.

Magdalene alone kept her serenity and even managed to comfort the others. She found her strength and courage in prayer, in frequent visits to church, in daily communion.

THE DREAM

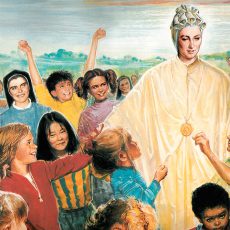

As Bresciani, one of Magdalene?s contemporaries, and her first biographer, writes, during the Venetian sojourn Magdalene ?had a dream, which had the form of a supernatural vision?, through which the Lord revealed to her the idea of her future Institute. She saw a lady in the company of six young women, dressed in brown habits, with black shawls on their shoulders and black bonnets on their heads.

Around their neck, each had a medallion of Our Lady of Sorrows. At a certain point, the lady summoned two of the young women and sent them amid a crowd of girls to teach catechism. To two others she indicated the wards of a hospital, inviting them to assist and comfort the sick. And finally she took the last two by the hand and led them into a large room. There was a bunch of poor, dirty, unkempt children. And she indicated the school as their area of work.

IN THE SERVICE OF CHARITY

In her Memoirs, Magdalene writes that one day, as she was attending Holy Mass – it was probably the feast day of St.Girolamo Emiliani – in the year 1795, the priest celebrating Mass, read a passage from the book of Tobit, extolling charity. The words had a striking effect on her and she was stirred ?to practise those works of charity which her status permitted her.?

From her many letters, we come to know of an extremely vast network of action in favour of persons and institutions. We find her present wherever some good was to be done, not only collaborating with other people?s initiatives, but also intelligently inspiring and promoting them.

She helped priests to introduce in the churches of her town adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, known as the Forty Hours. Through her connections with influential friends, she invited competent speakers from other areas to give talks, spiritual exercises, missions in Verona and outside. She helped organize conferences and monthly retreats for priests.

Together with Don Pietro Leonardi, she promoted Sunday catechism for the servants of noble families, and for barbers? apprentices who, because of their working hours, were unable to participate in Christian doctrine courses held in the parishes.

She was actively involved in the campaign to modify women?s fashions. For Magdalene, fashion was an important battle for ?attracting the divine blessings on countries? and preventing much offence to God. Among the young women of the Veronese nobility, she promoted what was known as the ?Company of the Immaculate?, whose members resolved ?to dress according to their condition, but always with modesty.?

Her greatest attention was for the poor and the sick. Not only did she give relief to all the destitute who came to the palace gate, but she actually went to look for them in their hovels. Accompanied by a servant and a maid, loaded with food, she would do the rounds of the most hidden nooks and crannies, bringing all sorts of provisions to the needy. Her charity became proverbial: ?When you see the young Marchioness of Canossa, run up to her, because she is sure to give you something.?

In order to help the needy and spur others to charity, she founded an unusual group known as the ?three coins?. Every member had to contribute three coins a week to the group. Several noblewomen she knew became members.

She found husbands for girls without dowries; she sent others into convents. She saved many girls from moral danger.

Not content with looking after her elderly uncles at home, she often visited hospital wards, overflowing with patients, especially young soldiers, who had been wounded in the various battles and daily skirmishes between the Austrians and the French. It was no mean act of courage to wander among the none too clean beds in badly ventilated, smelly wards among people covered with festering sores. Magdalene joined the Hospital Brotherhood, recently founded by Don Leonardi, and soon became the soul of the organization. Together with the founder, she drew up the regulations governing the Brotherhood which was to spread to other cities. She spent several hours a week at the bedside of the sick, giving out together with clothing and other necessities, words of comfort and faith, a smile of hope.

One day in the hospital ward she met Countess Carolina Trotti Durini from Milan who devoted herself to caring for the sick of her city. A warm friendship was born between the two women, fostered by an intense exchange of letters. For several years, the two friends stimulated each other towards sanctity, exchanging experiences and material help for the benefit of the needy.

For a period, Magdalene cultivated the idea of joining Don Leonardi, who had opened a home for abandoned boys and girls in Verona. But, in the course of a meeting, Msgr. Avogadro, her bishop, urged her to work alone and to dedicate herself preferably to the education of young girls in schools of charity. And, although she felt a natural repugnance for this type of service, she : decided to comply with her bishop?s wish. On the other hand, Don Libera too had urged her to undertake this same activity just before his death.

THE CANOSSA RETREAT

At the beginning of 1799, Magdalene gathered two young girls exposed to the dangers of the street and housed them temporarily at her own expense with a companion.

In March 1802, she moved them to a house in the Filippini area of the city, along with a third girl, originally from a noble family, who had ended up in ?a place of evil repute.? She then managed to convince two other companions to place themselves at the service of the girls and bought a house in the parish of San Zeno, the filthiest and most infamous part of the town, with the intention of opening a school also for external pupils. Unfortunately, Magdalene herself had to continue to live at Canossa Palace, but she spent almost her entire day with her girls. Her first concern was to form her companions in the Christian spirit and, for this purpose, she drew up together with them an outline of religious life. She was happy to look after these children and did not disdain to wash them, comb their hair and remove the lice. To those who were surprised in seeing the Marchioness of Canossa performing such humble tasks for her little ragamuffins, she would answer: ?Just because I was born a Marchioness, does that mean I cannot have the honour of serving Jesus Christ in His poor??

Meanwhile, her spirit alternated between moments of hope and despair. What worried her most was the search for teachers, for they came and went, in quick succession. Only the two most faithful, Matilde Bonioli and Matilde Giarola, stayed on. As the Marchioness remarked somewhat bitterly: ?There is no shortage of pious women, but real vocations are not so easy to find.? Therefore, her urge to leave Canossa Palace was stronger than ever. But her uncles, now old and ill, insisted on her staying.

Her brother, Bonifacio, though looking for a companion, could not make up his mind to marry. The weight of the house continued to rest entirely on her shoulders; not to mention Carlino, who still considered her his mother and ?always kept her very busy?.

In 1804, Bonifacio married the Countess Francesca Castiglioni in Milan. Magdalene immediately loved her ?as a sister? and soon handed over the running of the house to her. The uncles died, and Carlino?s father piaced him in the hands of a tutor.

?Freed from her ties?, again she felt her ?old dreams? to operate in the field of charity, dedicating herself to the most urgent needs of the poor, above all the religious and moral needs, absolutely convinced, as she was, that:

?THE LORD WAS NOT LOVED BECAUSE HE WAS NOT KNOWN ?.

She felt that the work she had already begun was on too small a scale. She needed to extend it, with the help of other hands, of other generous companions. But to do this, she had to leave home. Unexpectedly, it was Napoleon who gave her a hand. In the year 1805, the Canossa family had, as usual, to offer him hospitality. Magdalene asked her family to give her permission to withdraw among her girls during the period in which the guest was to stay at Canossa Palace. Permission was granted. On this occasion too, Magdalene was introduced to the Emperor, who learned from Prince Eugenio Beauharnais that, while her sisters were married, she busied herself with works of charity. Napoleon commented out loud: ?You see? Although a woman, this lady has found a way of being useful to the state?

The Emperor met Magdalene on various other occasions and always had for her words of esteem and praise for her charitable works.

Once he had left the palace, the Marchioness arranged for her uncle, Girolamo, and brother, Bonifacio, to be informed through their confessors that she would not be returning home any more. It was the end of the world. They would place no obstacle between her and what she called ?her vocation?, provided she found a more suitable dwelling and settled all her economic affairs. Magdalene, so as not to arrive at a complete break with her family, went home ?very determined, however, to continue along her path.? She immediately started looking for a suitable building. Her eyes fell on the monastery of San Zeno, which had become State Property after the suppression of the Augustinian Sisters. She got all her ?highly placed? acquaintances in Verona and in Milan to help her overcome the many bureaucratic obstacles which even then created numerous problems each day.

She had to persevere tirelessly for two years before obtaining the Decree of Assignment, issued on April 1, 1808.

FOUNDRESS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY

When on May 7, 1808, Magdalene moved into one o f the small, bare cells o f the ex-Augustinian convent, she had just turned thirty-four. She was in her prime. The trials of her life and vocation had tempered her. She was ready to start a completely new life.

Along with the three companions Matilde Bonioli, Matilde Giarola e Aniela Traccagnini, she also brought Domenica Faccioli and Leopoldina Naudet, who was looking for a temporary place in which to seek shelter with some companions before starting the Institution which she felt she was called to found.

The doors of the ex-convent were opened to the girls and women of San Zeno on May 8. The house was immediately filled to overflowing. The school and the catechism classes were soon organised and, a little later, also assistance to the sick in the hospitals and the formation of the young women to be a teacher in villages.

The Work extend the range. Magdalene opened a new communities in Venice (1812), in Milan (1816), in Bergamo (1820), in Trent (1828).

In 1819 the Institute obtained ecclesiastic recognition and the pope papa Leon XII approved “The Rules” of the Daughters of Charity, 23 of Decembre 1828.

MOTHER

Now that the Institute had been approved by the Pope, even though not finally, Magdalene felt a stronger commitment to help her daughters to grow in accordance with their specific vocation. There are some wonderful examples of this in her extensive correspondence. Magdalene wrote hundreds and hundreds of letters to her Sisters and had countless meetings with them. Despite the tremendous difficulty encountered in travelling, her many practical worries and. problems, and ill health, she unceasingly tried to help her daughters as much as she could, encouraging, guiding, comforting and reassuring them constantly. Margherita Rosmini, the sister of the philosopher, who had become a Daughter of Charity, wrote thus to her brother: ?Her disposition is always the same, cheerful and gentle with everyone. Her charity for all is amazing and her profound humility, not to mention the many other virtues she possesses to the highest degree?. It was a celebration in every community whenever Magdalene came to visit. She ardently desired that ?union and joy? should reign in every one of her houses. She frequently recommended union and charity. ?You can?t imagine what consolation I experienced when I heard of your union of hearts and the peace which reigns among you… I feel that ten years have been added to my life.

She was very close to the Superiors, encouraging them when they had problems, reassuring them that in carrying out their duty they were growing in sanctity.

Going through the many letters that Magdalene wrote to her daughters, we see the radiant expression of a vigilant and affectionate mother, ready to advise and comfort, concerned about her children?s spiritual development but not forgetful of their material needs.

It is not surprising then that Magdalene should have been so admired and loved not only by her daughters but by all those who knew her.

FOUNDRESS OF THE SONS OF CHARITY

Burning with ardent charity for God and for her fellowmen, Magdalene felt the need to extend her apostolic activity beyond the sphere of girls and women. Men and boys also were in need of fatherly guidance, above all for their moral and spiritual growth. There were too many stray children on the streets, many young people found themselves unprepared to face life.

In 1800, in the prime of her youth, Magdalene had drawn up a Plan for the establishment of a Congregation with a twofold family, male and female.

In 1800, in the prime of her youth, Magdalene had drawn up a Plan for the establishment of a Congregation with a two fold family, male and female. But in the historical development the opposite tool place: the Sons of Charity were born many year’ after the Daughters.

23 of May 1831 was opened Oratorio of the Institute of the Sons of Charity in Venice, close by the parish of Saint Lucia. It was a realizzation of the plan that Magdalene had inspired since 1799.

PROMOTER OF THE LAITY

The Marchioness, after two years from openind the house in Bergamo, in 1822 she was to start the first training course for rural teachers, for young women who came from the countryside and intended returning there to teach.

Several decades before any government intervention, Magdalene was already promoting courses which gave young girls graduating from them a diploma which authorised them to teach in the primary schools around the countryside. They lived in the Canossian Houses for the seven-month course, during which they learned to teach and also received a good spiritual and apostolic training.After the course, they returned to the rural areas and becoming collaborators of the Daughters of Charity in their service to others.

Well ahead of her time, through her rural teachers, Magdalene was among the first to promote the education of the people and to encourage the laity to collaborate generously in the apostolate of the Church. At the same time, driven by charity ?which is a fire that spreads out and seeks to embrace all? as she often said, the Marchioness started Spiritual Exercises for Ladies of the Nobility.

She knew from experience how useful the work of a noblewoman could be for salvation both in her own house and in other environments.

The Spiritual Exercises became a suitable ?for arousing in them the spirit of charity?. Yearly courses were also organised for girls and women of the populace, and for teachers, with great spiritual advantage for all. Magdalene, a truly apostolic soul, never felt satisfied. She was urged to constantly go forward, reaching as far as love could go: everywhere. This all-embracing desire to involve everything in the dynamism of love later led to the foundation of the Tertiaries of the Daughters of Charity, who were both lay women and religious.

Don Antonio Rosmini, who had known her well would hold her up as an example to his friends saying that in practising charity they should ?remember that good lady of Canossa, who unceasingly preaches that in the works of God one must have a generous spirit and undertake everything that is possible for His glory?.

TOWARDS THE END

Magdalene?s health had never been good but during her last years no one failed to notice how tired and weak she had become. Nevertheless she continued her numerous travels to assist the houses and to deal with lots of affairs. She sustained also the fatique of the Spiritual Exercises for the Ladies.

When she had got seriuously sick, she felt the need to express her final farewell to the Sisters of the Institute in a letter revealing a wonderfully affectionate spirit with no sign of sentimentality. It is a serene good-bye with heartfelt recommendations to love and be loyal to their vocation. She urged them to observe the Rules and to love obedience and humility and concluded with a final loving remembrance for those who had constantly occupied her thoughts and for whom she had unceasingly toiled in her apostolate: ?I recommend my beloved poor to you as much as I possibly can; try to ensure that one day they will be able to enjoy the Lord, and do so through your instructions, prayers, charity and hard work.? Her last words contained reference to her two greatest loves: ?I leave you all in the Heart of Mary Most Sorrowful, our beloved Mother. I wish that God would enkindle you with His holy and divine love.? It was her final will. But she did not stop her activity. In March she was able to return to Verona. She found there lots of job. She started at once, though, dictating letter after letter so as to answer the many that had piled up on her table during her absence. ?There is no time to lose,? she said, ?we must hurry!? At the end of the month she assisted the Spiritual Exercises of the Ladies but her cough and temperature never left her.

Maddalena finished her life so intense and fructuous at the age of the only 61. She died in Verona 10 of April 1835, Friday before Palm Sunday, surrounded by her spiritual daughters.

SAINT

Magdalene was heroic in practising all Christian virtues, but she stood out above all for her humility and charity. With this meaningful expression: ?humility in charity?, Pius XI synthesised ?the most beautiful and exquisite feature of this wonderful woman, of this pure virgin?, in his speech of January 6,1927, in reading the Decree of the heroicity of her virtues. On December 7, 1941, Pius XII, during the dark period of the second world war, raised her to the glory of Bernini proclaiming her Blessed. On October 2, 1988 she was canonised by John Paul II who told about her: ?charity devoured her as a fever?.

EPISTOLARIO

Her epistolario is rich of 3000 letters and her autobiografical notes help us to understand how much ardor was in her faith and her charity. The motor of her actions was love to Jesus Christ and her dedication for the neighbours for whom she had offered all her fortune and an energy.